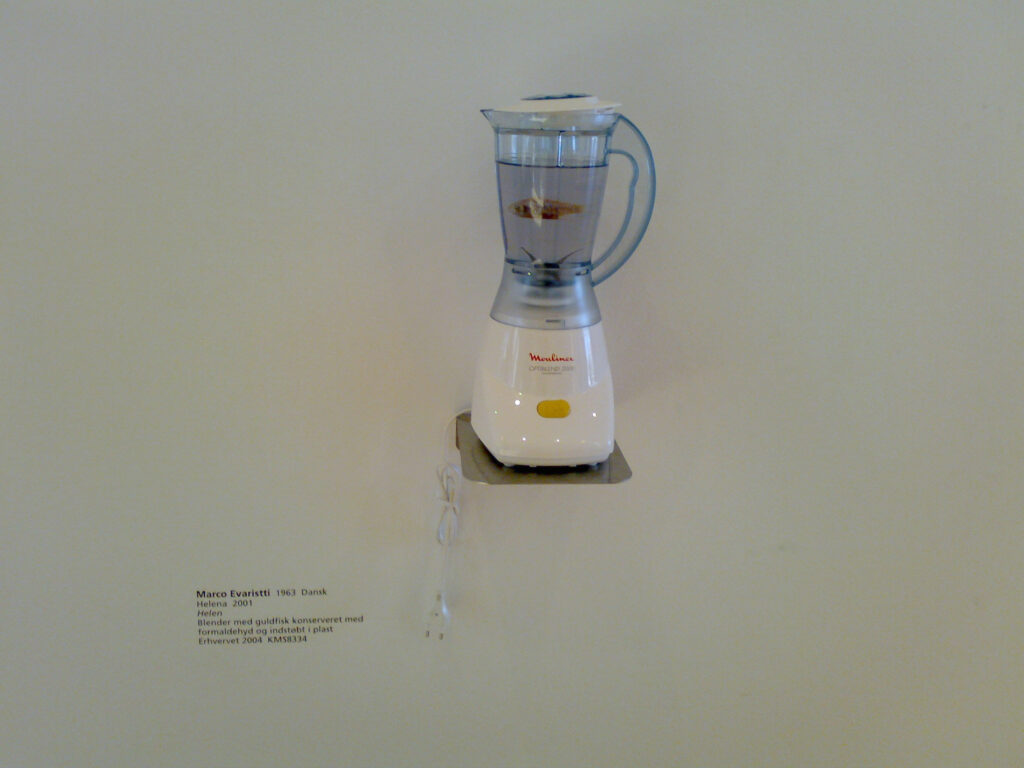

In the pristine white halls of the Trapholt Art Museum in Denmark, visitors in 2000 encountered a display that offered them a shocking power. On a simple table stood ten ordinary Moulinex blenders. Inside each glass pitcher swam a live goldfish, circling in the clear water.

The appliances were plugged into the wall, and the “ON” buttons were fully functional. The artist, Marco Evaristti, had created an installation titled Helena, but the exhibit was not merely for viewing. It presented a tangible, lethal choice to every person who walked by.

The Power to Kill

The premise was terrifyingly simple. The museum did not employ guards to stop anyone from touching the displays. Instead, the exhibition handed the moral burden directly to the public. Visitors could admire the fish, ignore them, or reach out and press the button. If they chose the latter, the sharp metal blades would spin instantly, reducing the living creature to a liquid in a fraction of a second.

For days, the tension in the gallery was palpable. Crowds gathered, staring at the bright orange fish and the tempting, dangerous machinery. The installation stripped away the distance usually found in art, replacing it with a raw, immediate ability to destroy life.

A Fatal Decision

It did not take long for the theoretical danger to become a reality. During the exhibition’s opening, someone made the irreversible choice. A visitor pressed the button on one of the blenders. The result was exactly as promised. The blades whirred, and the fish was gone, transformed instantly into a murky suspension.

The act triggered an immediate uproar. Journalists and photographers who had gathered for the event documented the aftermath. The news spread quickly, moving beyond the art world and into the realm of public outrage. Animal rights activists condemned the museum for facilitating the slaughter of animals for entertainment.

The Law Steps In

The controversy quickly escalated into a legal battle. Police arrived at the museum and ordered the staff to disconnect the electricity to the blenders. When Museum Director Peter Meyer refused, citing artistic freedom, the authorities seized the appliances. Meyer was subsequently charged with animal cruelty, facing a fine and a criminal record.

The case went to court, turning a local art exhibit into a national debate on ethics and law. The prosecution argued that the installation treated living beings as disposable objects. However, the defense called upon veterinary experts who testified about the mechanics of the death. They confirmed that the powerful blenders killed the fish so quickly—in less than a second—that the animals did not suffer.

Based on this technicality, the court acquitted Peter Meyer. The judge ruled that because the death was instantaneous and painless, it did not meet the legal definition of cruelty. The blenders were returned, but the story of the fish that swam above the blades remained a permanent chapter in art history.