In the early 1970s, at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, American psychologist Harry Harlow designed a device to break the mind of a living creature. Technically, the instrument was called a “vertical chamber apparatus.” However, Harlow insisted on using the darker name he had coined for it: the “pit of despair.”

His objective was not to study physical endurance, but to induce a state of crushing psychological depression in rhesus macaque monkeys. He aimed to simulate human psychopathology in a controlled setting, and the machine he created proved terrifyingly effective at doing exactly that.

The Design of the Well

The apparatus was a stainless steel trough with sides that sloped downward to a rounded wire mesh bottom, resembling a funnel. It was designed specifically to prevent the monkey inside from climbing up or seeing anything outside.

The animal had access to a food box and a water bottle holder, but nothing else. Once placed inside, the monkey was completely isolated from the world. There was no light, no sound from other animals, and no visual stimulation. Harlow’s goal was to break the animal’s connection to its environment entirely, creating a sensation of being “sunk in a well of despair.”

Days of Darkness

Harlow placed young monkeys, ranging from three months to three years old, into the chamber for varying periods. Some remained for thirty days, others for six months, and some for a full year. Most of these subjects had already bonded with their mothers or peers before the experiment began.

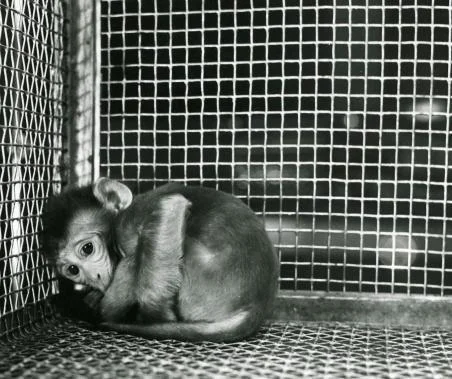

Within a few days of confinement, the monkeys stopped trying to escape the slippery walls. They curled into tight balls in the corner of the wire mesh floor. They ceased moving. They barely ate. Harlow described their condition as a state of “helpless hopelessness.”

Psychological Death

When the researchers finally removed the monkeys from the chamber, the animals did not recover. They did not play, explore, or interact with other monkeys. Instead, they remained huddled in the corner, rocking back and forth or clutching themselves. Harlow noted that twelve months of isolation “obliterated” the animals socially.

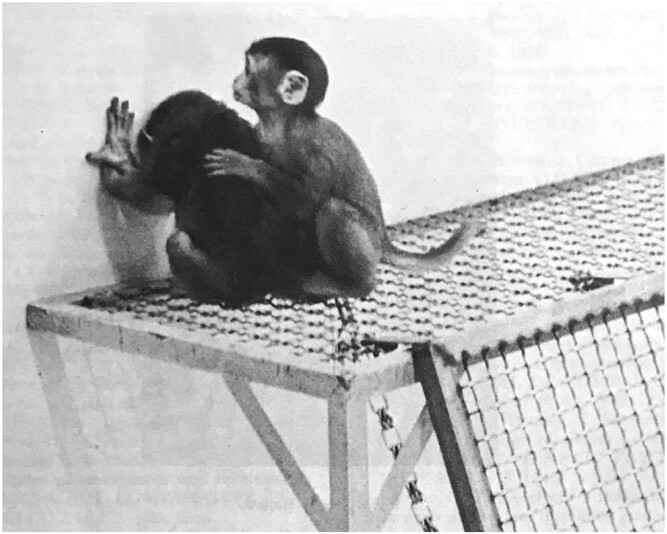

They were physically healthy but psychologically destroyed. When placed with control groups who had not been isolated, the “pit” monkeys were terrified and often attacked by the healthy ones, unable to defend themselves or signal submission.

Changing the Rules

The extreme nature of the experiment drew immediate attention. While Harlow argued that understanding human depression justified the method, the condition of the monkeys disturbed students and fellow scientists. One of Harlow’s former students, William Mason, described the work as violating ordinary sensibilities.

The visible suffering of the subjects in the pit of despair played a direct role in the formation of modern ethics committees. The criticism following these specific tests helped propel the implementation of new regulations regarding the treatment of laboratory animals in the United States.