A substance existed that was worth three times its weight in gold. In the ancient Mediterranean this was not a rare gemstone or a precious metal. It was a liquid extracted from the rotting glands of predatory sea snails. Tyrian purple defined the height of luxury for millennia.

This industry was built on millions of crushed mollusks and a stench that could be smelled from miles away. The process to create this hue was as gruesome as the result was vibrant. It involved a chemical transformation that turned a milky secretion into a deep and permanent violet that never faded.

The Secret of the Murex Snail

The production centered in the Phoenician city of Tyre. This city is located in modern-day Lebanon. Workers harvested two specific types of sea snails known as Bolinus brandaris and Hexaplex trunculus. Each snail possessed a small gland that produced a tiny drop of clear fluid.

To collect enough for a single garment tens of thousands of snails were required. Historical records from the Roman era indicate that 12,000 snails yielded only 1.4 grams of pure dye. This massive labor requirement ensured the price remained unattainable for almost everyone except royalty.

A Recipe of Salt and Sunlight

The extraction process was documented by the Roman writer Pliny the Elder. After harvesting workers broke the shells to remove the glands or crushed smaller snails whole. These remains were placed in large lead vats filled with saltwater and left to simmer for ten days.

As the mixture decomposed it released a potent odor of rotting fish. Exposure to sunlight and air triggered a photochemical reaction. This shifted the color from clear to yellow and then green and finally a deep reddish-purple. The exact timing of this exposure determined the final shade.

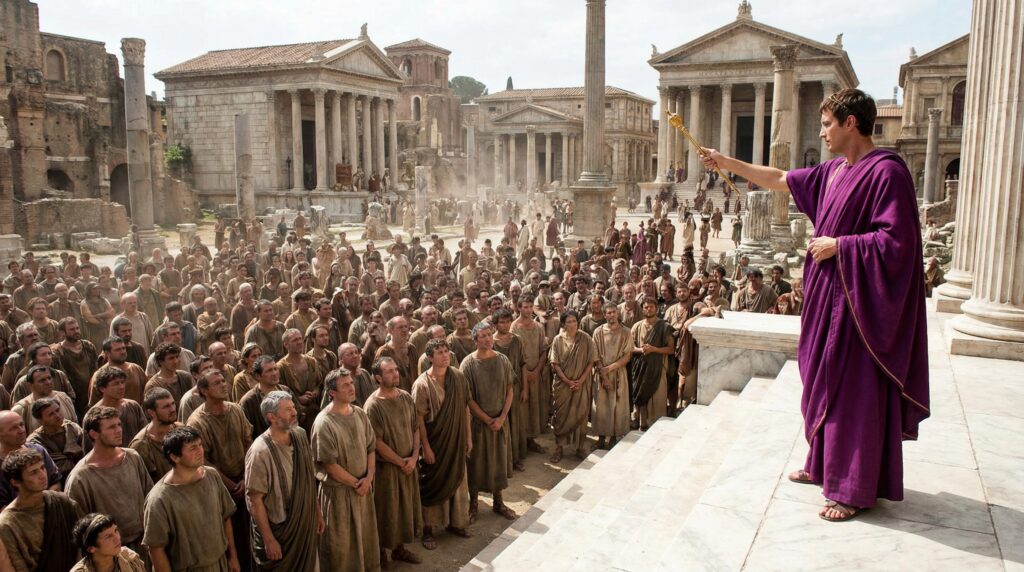

Laws of the Imperial Purple

Because the dye was so costly Roman emperors established strict laws to control its use. During the reign of Diocletian a pound of purple-dyed wool cost 50,000 denarii. The same weight in gold cost 72,000 denarii. Eventually Nero decreed that only the emperor himself could wear the color.

Anyone else caught wearing the hue faced severe penalties. These included the confiscation of property or death. The color became a legal identifier of rank. It was restricted by the state to maintain its exclusivity.

The End of an Era

The industry flourished for over 2,000 years until the fall of Constantinople in 1453. When the Ottoman Empire took control of the region the complex production secrets began to vanish. The high cost and the specialized knowledge required to process the snails led to a decline in production. By the time synthetic dyes were discovered in the 19th century the traditional method of boiling sea snails had largely disappeared from the Mediterranean coastline.