Long before the era of call centers, social media callouts, or one-star online reviews, a man named Nanni faced a frustrating ordeal that would sound familiar to many modern shoppers. In the southern Mesopotamian city of Ur, located in modern-day Iraq, Nanni found himself cheated by a merchant who failed to deliver the quality goods he had promised.

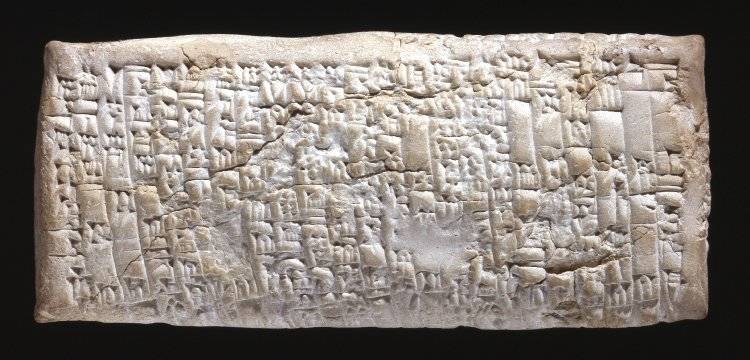

Instead of typing a furious email, Nanni took the time to etch his grievances onto a clay tablet in cuneiform script. This artifact from 1750 B.C. now resides in the British Museum and serves as the oldest recorded customer service complaint in human history.

The Broken Promise of Fine Copper

The dispute began when Nanni agreed to purchase a shipment of copper ingots from a businessman named Ea-nasir. Ea-nasir was a member of the Alik Tilmun, a guild of merchants based in Dilmun, and he presented himself as a prominent trader. He promised Nanni that he would provide fine quality copper ingots to an intermediary named Gimil-Sin. However, the transaction did not go according to plan.

When Nanni’s messenger arrived to inspect the goods, Ea-nasir presented ingots that were substandard. To make matters worse, the merchant was rude and dismissive. According to the translation by Assyriologist A. Leo Oppenheim, Ea-nasir told the messenger that if he wanted to take the bad copper, he could take it, but if not, he should go away. This blatant disregard for the agreement infuriated Nanni and prompted him to document the event permanently.

Insults and Dangerous Journeys

Nanni’s letter reveals that the poor quality of the copper was only part of the problem. He felt personally insulted by the way Ea-nasir treated his staff. Nanni had sent messengers to collect his money bag, but Ea-nasir sent them back empty-handed multiple times. This was not a simple errand, as the messengers had to travel through enemy territory to reach the merchant. Nanni asked in his letter why he was being treated with such contempt, especially considering the large investments he had made.

The tablet details that Nanni had given 1,080 pounds (490 kilograms) of copper to the palace on Ea-nasir’s behalf. Another individual named Umi-abum had contributed a similar amount. Despite these significant sums, Ea-nasir focused on a trifling debt of one mina of silver, which is approximately 1.1 pounds (0.5 kilograms). Nanni found it outrageous that the merchant would speak so arrogantly over such a small debt while holding onto much larger quantities of copper owed to him.

A Serial Offender in Ur

Nanni was not the only person who had trouble with this particular merchant. Archaeological evidence suggests that Ea-nasir had a habit of upsetting his clients. Another tablet discovered by researchers was written by a man named Arbituram. He sent a note demanding to know why he had not received the copper he paid for and threatened to recall his pledges if the goods were not delivered.

The British Museum holds the tablet from Nanni as a record of these events. It ends with an ultimatum. Nanni declared that from that point forward, he would not accept any copper that was not of fine quality. He warned Ea-nasir that he would select ingots individually in his own yard and exercise his right of rejection against any substandard pieces. The detailed account on the clay tablet remains a factual record of business malpractice in the ancient world.