On January 1, 1913, the United States Postal Service launched a revolutionary new service that connected rural America to the rest of the world like never before. The Parcel Post service allowed millions of citizens to ship large packages for a fraction of previous costs, bringing goods directly to their doorsteps.

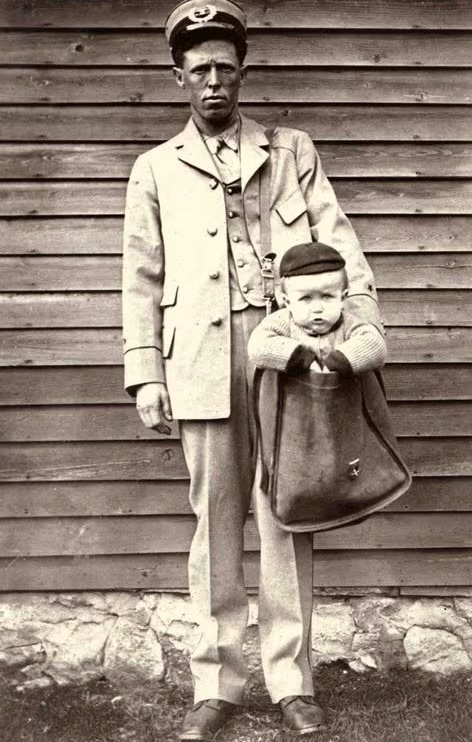

However, amidst the excitement of shipping farm produce and dry goods, postal officials overlooked one critical detail in their regulations. They had defined what could not be mailed, but they had not explicitly forbidden the shipping of humans. This bureaucratic oversight launched a brief, bizarre period where parents legally handed their children over to the mail carrier for delivery.

A Loophole in the Law

The regulations for the new Parcel Post service were vague. The rules stated that packages could not exceed 11 pounds, but they did not specify that the “package” had to be an inanimate object. The only living things explicitly permitted were bees and bugs, yet the language did not strictly prohibit other living cargo. In rural communities, families trusted their mail carriers implicitly.

These civil servants often provided the only daily contact for remote households, sometimes delivering medicine or checking on the sick. Consequently, when parents realized that postage was cheaper than a train ticket, they saw a practical solution for transporting their offspring.

The First Special Delivery

Just weeks after the service began, a couple in Ohio named Jesse and Mathilda Beagle became the first confirmed parents to utilize this unusual option. They wanted to send their infant son, James, to his grandmother in Batavia, a few miles away. The Beagles arrived at the post office with their 8-month-old child, who weighed just under the 11-pound weight limit.

They paid 15 cents for the postage and even insured the boy for $50. The local postmaster accepted the “package,” and the mail carrier successfully delivered baby James to his grandmother’s doorstep, kicking off a series of copycat mailings across the country.

Seventy-Three Miles for the Price of a Stamp

The most famous instance occurred a year later in Idaho. On February 19, 1914, a four-year-old girl named Charlotte May Pierstorff needed to travel from her home in Grangeville to her grandparents’ house in Lewiston. The journey covered 73 miles, and a train ticket was expensive.

Her parents noted that May weighed less than the maximum weight limit for packages, which had been increased since the service started. They attached the necessary postage stamps to her coat and handed her over to the railway mail service. Fortunately, she did not travel in a canvas sack; she rode in the mail car with a clerk who happened to be her mother’s cousin.

Closing the Post Office Nursery

These incidents generated national headlines, prompting confusion among postmasters. While local carriers often allowed the practice out of kindness or adherence to the strict letter of the law, federal officials were less amused. Reports surfaced that May Pierstorff had been mailed at the “chicken rate,” highlighting the absurdity of the situation.

Finally, in June 1913, the Postmaster General officially issued a regulation stating that children were not mail. Despite this decree, sporadic attempts to post toddlers continued for several years until the rules were strictly enforced, ending the strange chapter of mailing children in America.